Katabatic wind

From the Greek for ‘going downhill’, a katabatic wind is also known as a drainage wind. It carries dense air down from high elevations, such as mountain tops, down a slope thanks to gravity.

This is a common occurrence in places like Antarctica’s Polar Plateau, where incredibly cold air on top of the plateau sinks and flows down through the rugged landscape, picking up speed as it goes.

The opposite of katabatic winds are called anabatic, which are winds that blow up a steep slope.

Cities own microclimate

Some large metropolises have microclimates – that is, their own small climates that differ from the local environment.

Often these are due to the massive amounts of concrete, asphalt and steel; these materials retain and reflect heat and do not absorb water, which keeps a city warmer at night.

This phenomenon specifically is often known as an urban heat island. The extreme energy usage in large cities may also contribute to this.

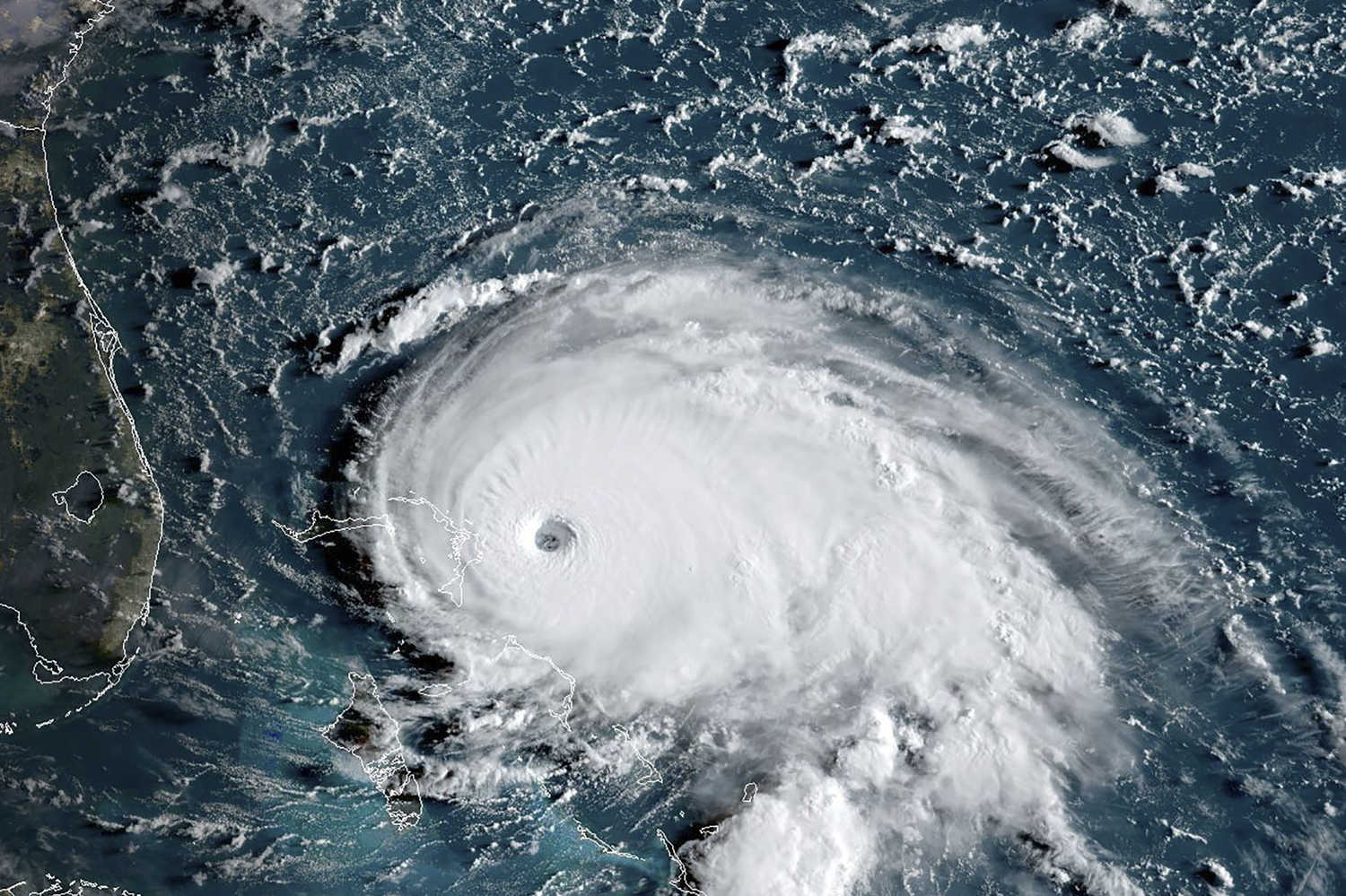

Hurricanes

Depending on where they start, hurricanes may also be known as tropical cyclones or typhoons. They always form over oceans around the equator, fuelled by the warm, moist air.

As that air rises and forms clouds, more warm, moist air moves into the area of lower pressure below. As the cycle continues, winds begin rotating and pick up speed.

Once it hits 119 kilometres (74 miles) per hour, the storm is officially a hurricane. When hurricanes reach land, they weaken and die without the warm ocean air.

Unfortunately they can move far inland, bringing a vast amount of rain and destructive winds.

People sometimes cite ‘the butterfly effect’ in relation to hurricanes. This simply means something as small as the beat of a butterfly’s wing can cause big changes in the long term. Read here Difference Between Cyclone, Hurricane and Typhoon!

Snow in Africa

Several countries in Africa see snow – indeed, there are ski resorts in Morocco and regular snowfall in Tunisia. Algeria and South Africa also experience snowfall on occasion.

It once snowed in the Sahara, but it was gone within 30 minutes. There’s even snowfall around the equator if you count the snow-topped peaks of mountains.

Giant hailstones

Put simply, giant hailstones come from giant storms – specifically a thunderstorm called a supercell. It has a strong updraft that forces wind upwards into the clouds, which keeps ice particles suspended for a long period.

Within the storm are areas called growth regions; raindrops spending a long time in these are able to grow into much bigger hailstones than normal.