The Titanic sinking became the most infamous shipwreck in history—but what really happened on that unusually calm night in the North Atlantic? Read on for some surprising Titanic”.

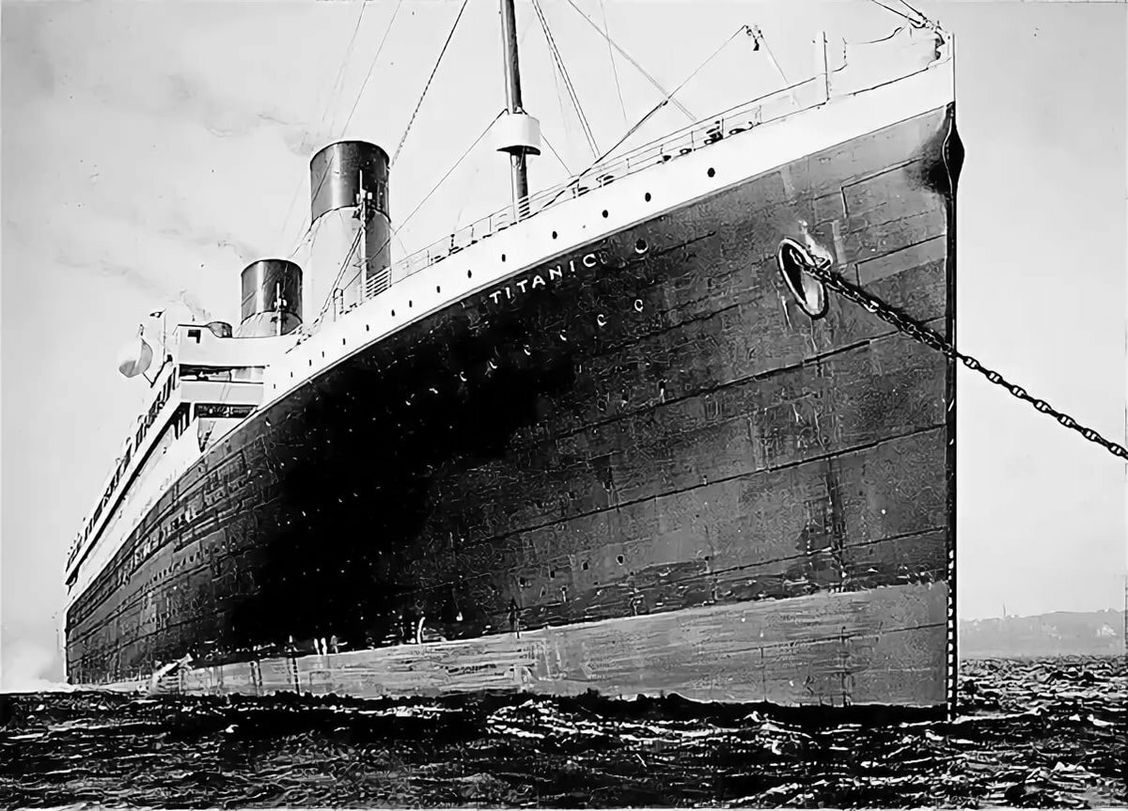

“Titanic was built for luxury, not speed

In the early 20th century, new technology and an increasing population of European immigrants allowed Britain’s largest passenger steamship lines to build the biggest and most opulent ocean liners then known. Liverpool-based Cunard launched the two fastest and sleekest liners, the Mauretania in 1906 and the Lusitania in 1907, capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean in record time. The White Star Line, hoping to compete with its main rival, countered by ordering three massive ocean liners—the Olympic”, “Titanic, and Britannic”. Built by the Harland & Wolff Shipyard in Belfast, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), the ships were designed to be the most luxurious liners afloat.

Everything on the Titanic was huge—except the number of lifeboats

"Titanic was the largest passenger ship of its time. Its steel construction was held in place by 3 million rivets weighing 1200 tons, while each link in the ship's anchor chains weighed 175 pounds. According to the British government's official inquiry, the ship carried about 1316 passengers and 885 crew on its maiden voyage (other sources have slightly different numbers), but only 20 boats, each of which could safely hold between 40 and 60 people for a total capacity of 1178. At the time, Board of Trade regulations for passenger liners required only 14 lifeboats on board. The Titanic had 14 lifeboats plus two cutters and four collapsible boats.

The plot of an 1889 novel bore eerie similarities to the events that would befall the Titanic"

The Wreck of the Titan, or, Futility, by little-known novelist Morgan Robertson, may not have predicted the Titanic's sinking, but it includes some uncanny coincidences. In the book, the most fabulous ocean liner ever built—the Titan (!)—is crossing the Atlantic on its maiden voyage when it collides with an iceberg and sinks. The Titan was 800 feet long; the Titanic was 882.5 feet. Both ships could reach speeds of 25 knots. Both sailed in April. Both could carry 3000 people, and both had far too few lifeboats.

Before the Titanic sinking, ocean liners encountered more icebergs than usual in the North Atlantic

Icebergs were a common sight between Ireland and Newfoundland, but a 2014 study published by the Royal Meteorological Society suggested that weather conditions produced more of them than average in April 1912. Freezing air from northeast Canada met the southward flow of the Labrador Current off the coast of Newfoundland, leading to a stream of icebergs that were swept farther south than was typical for most of the 20th century. "In 1912, the peak number of icebergs for the year was recorded in April, whereas normally this occurs in May, and there were nearly two and a half times as many icebergs as in an average year," the authors wrote.

On April 14, 1912, the Titanic received several wireless messages from other ships warning of ice along their routes, but they never reached the Titanic's captain.

Hundreds of Titanic survivors were rescued—but more than a thousand perished

Of the 2201 passengers and crew on board, just 711 survived the Titanic sinking, a death toll of 1490 according to the British government's figures. (Other inquiries found 1503, 1517, and as high as 1635 deaths). First-class passengers suffered the fewest casualties—203 out of 325, or 62 percent, survived. In second class, 118 of 285 passengers, or 41 percent, survived. And in third class, just 178 of 706 passengers, or 25 percent, made it out alive.

The Titanic sinking left tragic "what if?" questions

Walter Lord summed up the chain of tragic—and avoidable—missteps that led to the disaster:

"If the Titanic had heeded any of the six ice messages on Sunday … if ice conditions had been normal … if the night had been rough or moonlit … if she had seen the berg 15 seconds sooner—or 15 seconds later … if she had hit the ice in any other way … if her watertight bulkheads had been one deck higher … if she had carried enough boats … if the Californian had only come. Had any one of these 'ifs' turned out right, every life might have been saved."

No one knew the exact location of the Titanic wreckage for 73 years

Several expeditions had tried and failed to discover the final resting place of the Titanic in the North Atlantic. In 1985, Robert D. Ballard, then a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and a French team led by Jean-Louis Michel of the research institute IFREMER finally succeeded. The U.S. Navy had secretly commissioned Ballard to locate two Cold War-era nuclear submarines that had sunk in the North Atlantic decades before—and Ballard agreed to help as long as he could use its technology to search for the Titanic in the same area.