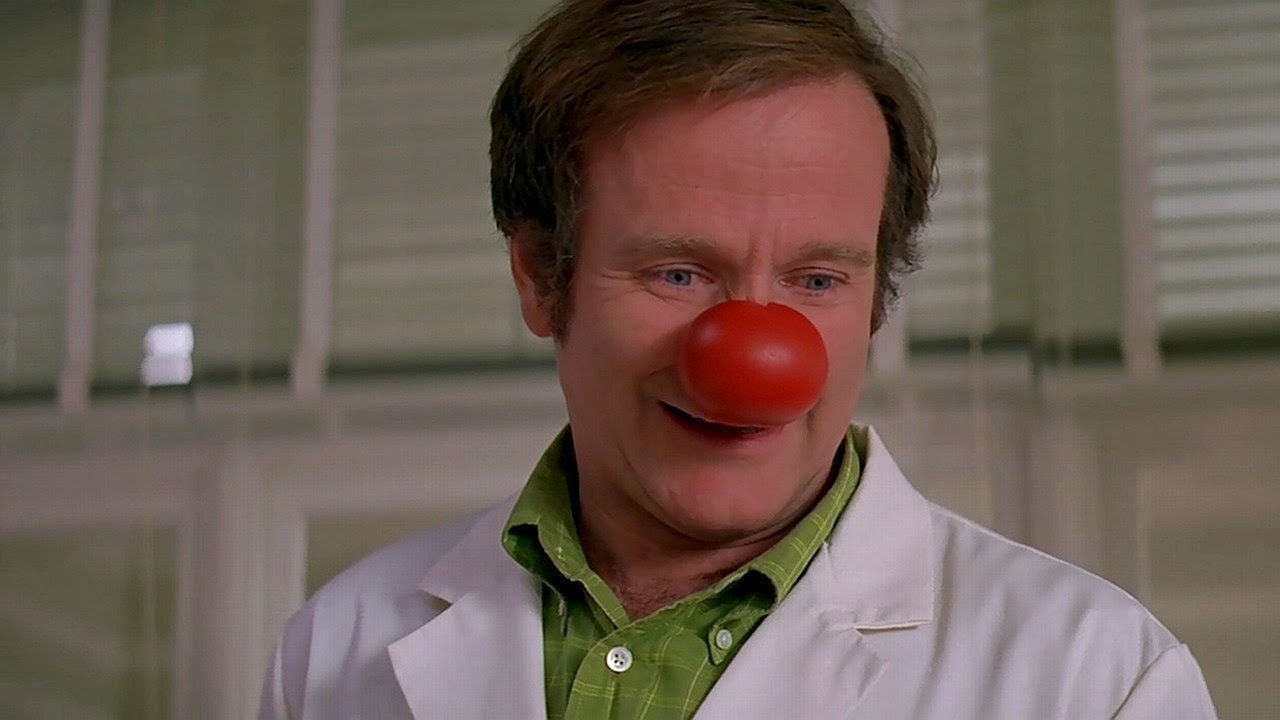

As a comedian, Robin Williams delivered a high-wire act of verbal dexterity balanced with an unpredictable physicality.

Williams said comedy is rooted in a ‘deeper, darker side’

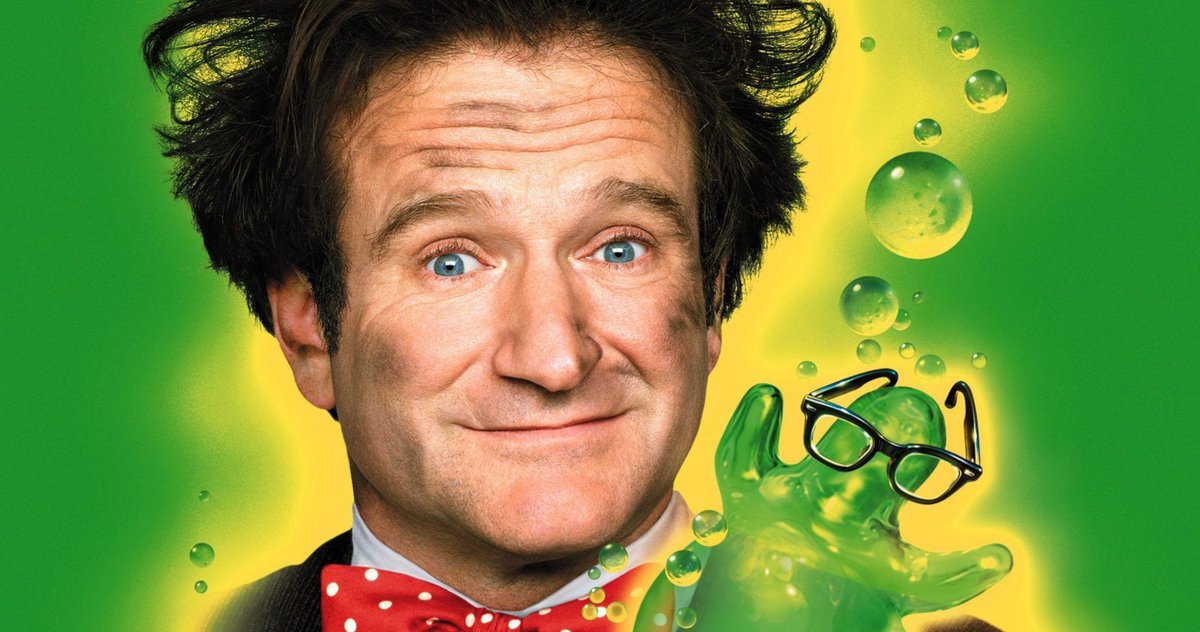

When Williams died in 2014 at the age of 63, the world mourned a stand-up comic and Oscar-winning actor who could make them laugh – and think – due to roles in television and film such as Mork & Mindy, Good Morning Vietnam, Mrs. Doubtfire, Dead Poets Society, Good Will Hunting, Jumanji, Aladdin, and The Birdcage. Audiences at Williams’ stand-up shows recall hilarity at the speed of an out-of-control freight train. According to good friend and occasional comedy partner Billy Crystal, doing a set with Williams “was like trying to lasso a comet.”

“For me, comedy starts as a spew, a kind of explosion, and then you sculpt from there, if at all,” Williams once said of his work. “It comes out of a deeper, darker side. Maybe it comes from anger, because I’m outraged by cruel absurdities, the hypocrisy that exists everywhere, even within yourself, where’s it’s hardest to see.”

To Williams, comedy was equally as addictive as drugs and alcohol

Williams had publicly addressed his struggle with alcohol and cocaine many times over the years, but comedy, the desire to get the laugh, land the joke, was also a type of addiction for the performer.

Drugs and alcohol became a need he couldn’t satisfy, not to elevate his zaniness on stage but for opposite reasons. “Cocaine was a place to hide,” Williams told People in 1988. “Most people get hyper on coke. It slowed me down.” When his first wife, Valerie, was pregnant with their son Zachary, he quit cocaine and alcohol. The death of his friend John Belushi from an overdose had also gave him the courage to kick his addictions. “His death scared a whole group of show-business people. It caused a big exodus from drugs,” he said. “And for me, there was a baby coming. I knew I couldn’t be a father and live that kind of life.”

Though he relapsed with alcohol and returned to rehab in 2006, he never touched cocaine again. Instead, he sought fulfillment in his roles. “It’s like he didn’t worry about anything when he worked all the time,” recalls his makeup artist Cheri Minns in the biography, Robin, by Dave Itzkoff. “He operated on working. That was the true love of his life. Above his children, above everything. If he wasn’t working, he was a shell of himself. And when he worked, it was like a light bulb was turned on.”

His children were also a source of joy to Williams, though he carried guilt for splitting his family due to his three marriages. In Robin, his children revealed they tried to help him free himself of the guilt, that there was nothing to apologize for. “He couldn’t hear it. He could never hear it. And he wasn’t able to accept it,” Zachary said. “He was firm in his conviction that he was letting us down. And that was sad because we all loved him so much and just wanted him to be happy.”

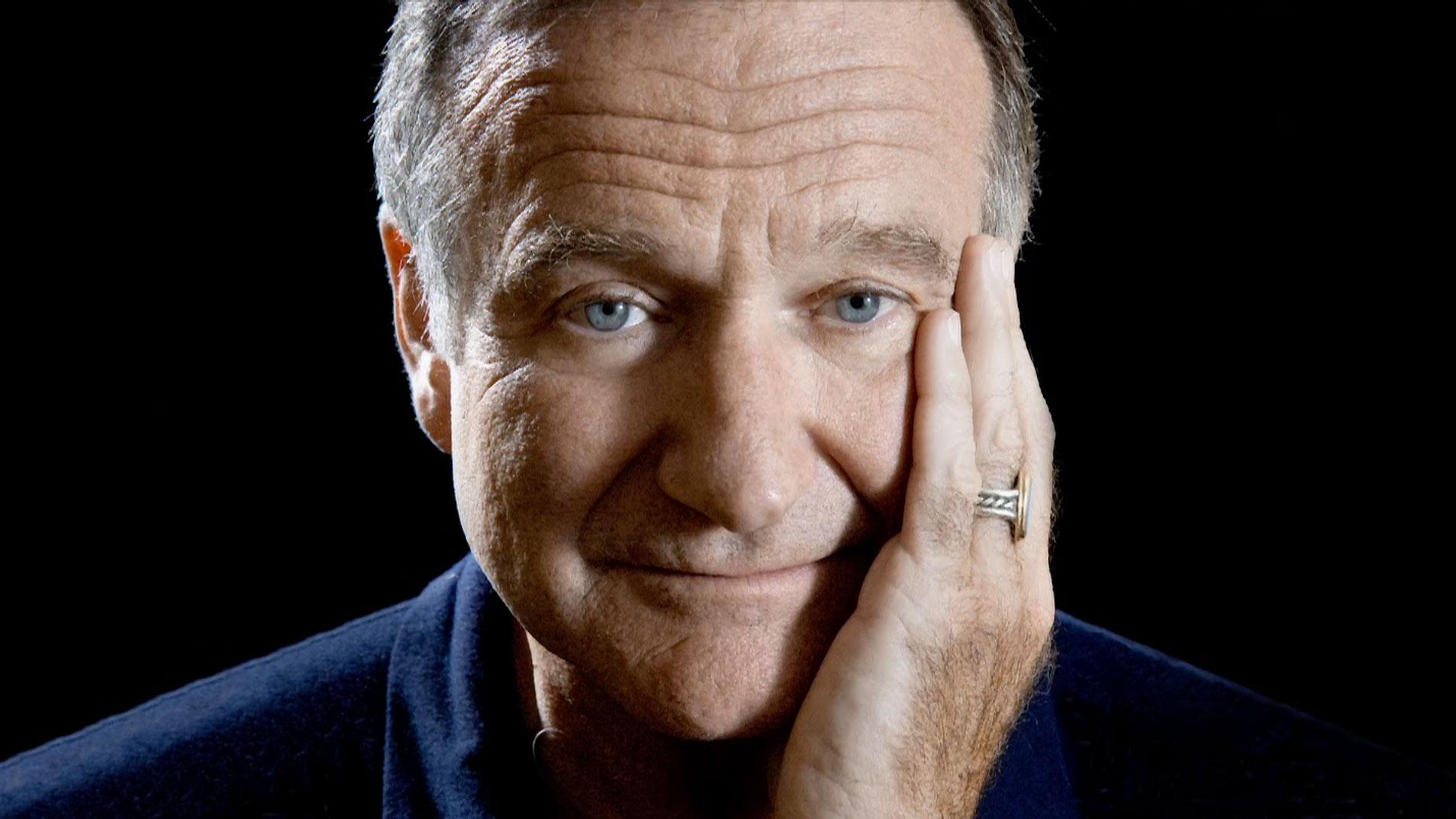

Towards the end of his life, Williams claimed he didn't 'know how to be funny' anymore

By late 2013 Williams was experiencing symptoms he did not know the cause of. He had become paranoid, could no longer remember his lines, experienced insomnia, and an impaired sense of smell, Schneider chronicled in a 2016 editorial she wrote for the journal Neurology. Extreme anxiety, tremors and difficulty reasoning soon followed.

In May, Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder. Doctors said they had drugs that could control his tremors and that he would likely live another decade.

On August 11, 2014, Williams was found dead in his California home. A release from the County Sheriff’s office following an autopsy revealed he had hanged himself. No alcohol or illegal drugs were found in his system. His publicist said prior to his death he was suffering from severe depression.